|

Book Recommendations

by Philip M. Williams

Commentary on Dr. Caroline Malone's English Heritage: Avebury Commentary on Dr. Caroline Malone's English Heritage: Avebury

Upon visiting Avebury years ago I purchased the English Heritage: Avebury. It has been an indispensible source book. The Neolithic Era has left scant evidence of the necessities of life, so we must speculate. I may not agree with some of the book's assumptions. The disagreement is slight. It is mostly a matter of perspective. Regardless, English Heritage: Avebury is a great source.

Diagram 75 & 76: Without these, it would be difficult to write of the building of Silbury Hill.

Photo 99: How better to describe Jake and Amy's consternation at digging at the base of the trench?

Photo 92: The very Antler pick Amy was forced to use on her first day of work.

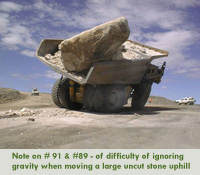

Diagram 91: Correct in its assumptions. However, gangs of men are inconvenient in moving large, un-cut stone. Large stones are not towed uphill. It is easier to raise it up in situ and then ease it down a slight grade, only to ease it up again, and again, in the same manner as locks are used on canals. # 3 and #4 would be attempted only by the truly incompetent. How would the incompetent get the stone there in the first place, and what would they be proving? However, section #6 is fine in possible number of stone movers, and in their joy of accomplishment. Diagram 91: Correct in its assumptions. However, gangs of men are inconvenient in moving large, un-cut stone. Large stones are not towed uphill. It is easier to raise it up in situ and then ease it down a slight grade, only to ease it up again, and again, in the same manner as locks are used on canals. # 3 and #4 would be attempted only by the truly incompetent. How would the incompetent get the stone there in the first place, and what would they be proving? However, section #6 is fine in possible number of stone movers, and in their joy of accomplishment.

Diagram 89: Correct in some of its assumptions. Ignores that one must use gravity to advance a project of such mass, even with an army of men, most of whom would be standing around, much of the time. (Please see Photo 70)

Diagram 88: Excellent view of greenhorns at work. In the environment shown, excavation skills increase rapidly. In common labor, the young are copy cats, just as they are in athletic events: tennis, skiing, swimming, diving, golf, etc. The behavior depicted is not reasonable over a thousand years. In all manual construction, knowledge based teamwork lightens the daily grind. Only the dimmest of souls would work in this manner, and soon they would quit, from lack of appreciation (ridicule), or would learn to work harmoniously with others.

Diagram 84: "The seams! The seams!" chants Peanut, the teacher.

Photo 70: Egad! I take my hat off to them, but would ask them to retire elsewhere. They know they are loafing. They know they are foolish, but they must follow orders. Raising a stone is not a pole dance. The lever is much too large. Multiple levers prevent the stone from twisting. Only a few men are actually doing anything (in this case fitting the lever under the stone). What is instructive about the photo is the sincerity of Alexander Keiller, which is compromised by the deep social chasm between those who worked with their hands, and those who did not. Some men, and women of the time: T. E. Shaw and Gertrude Bell for example, bridged that gap, but they did so in places other than in Great Britain.

This social disconnect, right up to the middle of the twentieth century, carries on into archeological speculation about prehistoric building technique. How does one know how to move a large stone by hand unless one has observed the action?

Piggott and Smith offer a treasure trove of good evidence. Sketch 25 and diagram 62 reveal the significance of vertical (as opposed to slanted) post holes in latitudes of 40 and higher. In those latitudes, light must be introduced by doors and windows. Optimization of sunlight for interior illumination was essential in the days before the light bulb. Further principles of construction are useful in the analysis and functions of postholes:

1st: Verticality of walls. This is well illustrated in diagram 62. Slanted walls preclude windows, for even a doorway makes part of the floor open to the elements. Vertical walls in northern climes demand that most buildings have both doors and windows. See sketch 25. In that sketch the domesticated animals look for companionship. A simple hurdle keeps them out. If a carpenter has the skills to make a door, he has the skill to make a window, because the framing of both is identical. Neither framed opening requires more than elementary building skill. Postholes, which mandate vertical walls, means that the weather is kept outside. A door is hinged from the side. A window is hinged from the top, allowing the shutter to give additional protection from the elements.

2nd: As shown in diagram 62, postholes indicates that walls easily may have considerable height. This versatility of design allows for a doorway to be of a height that a man carrying a bundle on his shoulder does not have to stoop for entrance. 25 indicates a doorway of suitable height.

3rd: Posts are connected by an upper "plate" or "sill", as is shown in 25. It is much easier to keep that plate at the same height around the circumference of a building. Higher walls lend themselves to more usable indoor space and simpler construction. Low walls use less material and are less work, so a hovel might have low walls. Even today not everybody lives in hovels.

4th: Precision of posts planted in post holes. Posts are planted perpendicular to the earth. A twig, or similar projection, is attached to the upper end of the post. A line, with a weight, is attached to that twig. The line runs a distance down the post.

A second twig is attached at a right angle, approximate, to the first twig. Equally a line with a weight is attached to that twig. The post will be perpendicular when both lines parallel the post, as the hole is in-filled.

Any builder who has studied the great stones knows that the original planters were aware of using weighted lines to establish perpendicularity, because if stones are out of vertical balance, they twist and fall.

Precision of verticality means precision of upper plate, since the distance between posts measured on the ground is equivalent to the distance between posts at the upper sill.

All posts, each and every one, with the single exception of Stonehenge, infer straight line connection. Postholes in a round must be studied very carefully. The genius of Stonehenge is that their upper plates, composed of massive stones, which they trimmed to a curve, overcame straight line connection. Wood cannot overcome straight line connection in a regular behavior. The great buildings of Avebury (the Sanctuary) are composed of straight line connections in the same manner as an umbrella encompasses straight lines.

Therefore, with the appropriate algorithm, a computer can identify which holes represent which buildings with a fair degree of probability. The probability that posts follow a straight line, and are regular, be it square or rectangle, is high, particularly where multiple holes infer that buildings were torn down and built again. Hovels are not built again. Any builder would say,"I can do better than that hovel."

The Postholes of Stonehenge

The postholes of Stonehenge have unique characteristics; the holes are filled with stone posts. The holes are topped with a stone upper plate. Stone posts in weathering conditions, unlike wood posts, do not change over time. Wood posts are unpredictable in weathering conditions. Under weathering conditions, wood posts connected by an upper plate, also of wood, are subject to rot.

The procedures for erecting a post and lintel structure is the same in stone as in wood. The skills of the builder who can measure precisely and who can cut to measure is not limited by the materials he uses. The measuring is the same, but the cutting is more time consuming. The advantages to the astronomer of having an instrument that changes little from season to season and from year to year is manifest.

Predictability is increased. Errors due to the weathering of wood are eliminated. The height of the stone lintel gives a precise datum line for the horizon. The center stand and the inner stand would be of wood, as they would merely be platforms for the observers. Marks on the stones most likely would be on the top of the sills.

The contrast between Avebury and Stonehenge is interesting. Please see essay on function.

Piggott would be elated that his precise measurements of post holes leads to further knowledge. Thank God for Piggott. That does not count for his analysis of stone tools. Actually the Stone Age should more accurately be called the Age of Wood. The Wood Age continued until about 1960. Stone was merely the edge of many tools. One throws away a stone shovel, a stone hoe, a stone plow, a stone bow. Stone is very important as an edge, or as a hammer, or the head of an axe, but a wood handle makes the ax many times more efficient. See # 43. Although skilled workers would use a mallet, if driving wood or stone, the concept is correct. The handle would be more useful if longer. Most axe handles average 3'. Most hammer handles are more than 1' and less than 2'. Their length has not changed since the Neolithic Age.

Stuart Piggott enclosed a photograph (ANCIENT EUROPE Tenth Printing, 1980 xx11 facing p. 155) the significance of which he intuited. That knife is not a weapon. It has a loop at the top of the hilt to allow it to function as a weight (see comment above). The unusual cross guards prevent its use as a normal knife, but they enable the hilt to store a twine line. The unusual knobs on the walking stick are inconsistent with native branching. They signify an artistic inversion of the design to perpetuate the molding. It is a measuring rod before the standardization of measures. One may spend hours pondering the meaning of this figure. The Nuraghic artists are famed for their realistic sculpture. This sculpture's accoutrements are symbolic indications of the figure's role in the world.

Illustration 7: Very good, if one were to take a series of photographs, year after year and to superimpose one atop another, in order to portray a process taking centuries. Also it presumes the initial creators visualized the completed project before it was begun. It also assumes a creative genius at the inception and no genius after. This initial genius commanded that no infilling was to take place until the whole shebang was completed, a thousand years later. The winding road to the top is a most difficult engineering feat because of the need to visualize height, width, depth, and pitch of a road winding upwards, before the height is present. It is difficult to conceive in progress, but makes for excellent training. If Silbury Hill is a work in progress, the learners become the teachers, year after year, and pass along, to those who wish to learn, the visual and mechanical skills needed to create a winding road up an incline. That task is no work for amateurs.

Photo 99

The importance of this photo cannot be underestimated. It is real. It is there. This trench is not the work of unskilled amateurs who take a few weeks off from stealing their neighbor's goods, from fratricide, matricide and general killing in order to dig a trench that does not function as a defensive rampart. To defend Avebury one would have to climb down that trench and back up again while invaders could perch on the rampart and shoot at all the fish in the barrel. As a training ground for would be-engineers it sorts out true workers from hopeful wannabes.

None of the above comments diminishes Ms. Malone's accomplishment. She forces one to think out the nuances of the building process, and to sweat out the effort to communicate everyday construction behavior to the non-builder.

I praise her work, and thank her.

Return to Top

Commentary on Julian Richards' English Heritage: Stonehenge Commentary on Julian Richards' English Heritage: Stonehenge

There are many books on Stonehenge, but few have the visual impact of The English Heritage Stonehenge by Julian Richards. Essentially, Stonehenge is a visual experience. It was all about vision when it was built, and it is all about vision now, around five thousand years later. The front cover of the 1996 edition is perfect for illustrating the conundrum of Stonehenge, because it is a photograph taken from where most of us have never been. That photo reveals the modern highway clipping it close, thus leaving Stonehenge visually clouded from the ground, and visually undisturbed from the air.

That conundrum for the innocent abroad is summed up by, "What is all the excitement about for these odd chunks of stone flung down in the middle of nowhere?" The world traveller who has been stunned by the imperturbability of the great pyramids, who has gasped at the glory of the Acropolis, and has wondered at the vastness of Hagia Sophia, who has been rewarded by the richness, seen from inside and out, of Canterbury Cathedral, may make nothing of Stonehenge.

Mystification is understandable, because while other World Heritage sites were designed by their creators to impress and inspire the observer, Stonehenge was merely a machine within the context of a larger community. The machine operators were the ancient observers, and they were interested only in observing the far flung phenomena, and had absolutely no interest in whether some passer-by was impressed with their machine. That is not why they had it built.

Exploring and revealing the larger community is a great strength of Stonehenge. It is to Julian Richards' credit that while awash in the cacophony of Stonehenge literature, he keeps his eye on what there is in the environs. Those environs add depth and perspective in understanding Stonehenge the site. One must appreciate Richards' astute juxtaposition of photos, charts, drawings, and sketches with his verbal descriptions. Taken together they reveal the complexities, the differences and the similarities among other earthworks and excavations of the whole incredible area.

Of course, like enjoying a hot fudge sundae with whipped crème topping, nuts and the ubiquitous cherry, after digesting, or at least swallowing, a roast beef dinner with Yorkshire pudding, one may drift off to the seductions of fantasy, when it comes to Stonehenge.

Take Professor Thom's "Megalithic Yard". It is unfortunate that Professor Thom's simple assumption that measurement is standardized undoes much of his good work. The common man is no different now than he was in the past. He does not take kindly to his units being standardized. A pinch of salt. A peck of apples. Off by a hair. And you want our units standardized? Take two bites out of that pile of earth. Give me a shovelful. OK, I can use a bundle of shingles, a gallon of gas, a liter! What about a mile, a kilometer? And so on. From a builder's perspective there is no need for a standard unit of measurement. Standard units are figures of commerce. They are imposed by a hierarchy in order to keep things up to standard. An architect needs a standard, but a builder can cut, and does cut, units to his own measure. His personal rule for his personal job prevents others from "taking off" his work.

If there were any units at Stonehenge, they functioned as memory aids. Stonehenge magicians depended upon their long term memory of the celestial past to predict earthly activities that occur in the future. The sun controls life and death of most growing things of the world, particularly above latitude forty. The moon controls the tides. But what do the stars control? How does the greater firmament control our life and health? Predicting these serious issues in order to reduce fear of the unknown was the art and science of Stonehenge. Julian Richards does not wander down these fantastical pathways, nor does he describe the bells and whistles of the medieval jester prancing on the boards of Shakespeare's Globe. What he accomplishes in Stonehenge is to set the stage for its complex society, a society that is far less fear driven than others of their time.

Return to Top

Commentary on Steven Pinker''s The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature Commentary on Steven Pinker''s The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window into Human Nature

This is a book to read more than once if one wishes to glean, wring, reap, tease out or harvest its bounty. The first time through will drive the reader to distraction, for Pinker goads one to precise word choice. The housekeeper may shake a rug. The thief may shake a leg. The dancer may shake, rattle and roll, yet nobody shakes up Linguistics more pleasurably than Professor Pinker.

Back in the mid-Twentieth Century, Linguistics hovered uneasily between Philosophy, Psychology, Mathematics, and English, or so it seemed. Words lacked life force. They were reduced to grammatical constructs. Grammar was the universal touchstone. Further, Linguistics was soured by word count. Individual use of words was of little interest. Cognition had no import. A Linguistics Major appeared a dyspeptic bet for a pupil trying to stay in College. Who wanted to fill out multiple choice questionnaires? How ironic that Sociology, known at times as group-think, would open the doors to the individual and bring life to Linguistics?

Linguistics now affirms that nuance and interaction of words and their meanings matter. It subjugates all languages to the empire of thought. It overleaps the constraints of time. At what age does one learn to remember and to deselect among hundreds of potential choices? In the biology of cognition, these expressions and repressions have an electrical and a chemical basis, but the linguist asks, "What does one see? What does one imply? What does one skirt?" For a poet, a novelist, an essayist, or any thinker, few works are more helpful than Pinker's The Stuff of Thought.

Word count makes a difference. The blessed computer spools out that number. It can be annoying to see that one uses the same word again, and it is entrancing to tangle, twist, or tussle with the analogue of metaphor as Stephen Pinker coasts into complexities of the human mind. Pinker's marshaling of not exact synonyms draws one into savoring each word for its essence, as surely as the starveling delights in the meat closest to the bone. So Pinker is both a distraction and a goad.

"Use more verbs!" he commands. "Try babble, bark, bellow, bleat, boom, bray, burble, cackle, call, carol, chant, chatter, chirp, cluck, coo, croak, croon, crow, cry, drawl, drone, gabble, gibber, groan, growl, grumble, grunt, hiss, holler, hoot, howl, jabber, lilt, lisp, moan, mumble, murmur, mutter, purr, rage, rasp, roar, rumble, scream, screech, shout, shriek, squeal, stammer."

How can one remember a train of thought, after visualizing a passage through one's internal thesaurus? Pinker is no pedagogpedagogue. He is a cinematographer who opens views to the world, and reveals their many faceted reality to explore how the mind works. In analysis of causes, effects and of implications, The Stuff of Thought is a text book of the findings of Cognitive Science.

The study of how the mind works has consequences for society and for morality. It identifies our differences and similarities with other things existing on our planet. No longer is Linguistics an antiseptic analysis of grammatical forms. It is fundamental to our intellectual life, and ranges through the fields of Psychology, Sociology, and Philosophy.

Although Pinker's linguistic exposition gleans the most delectable tidbits, and grubs out the most abstruse of ancient and modern thought, its great contribution to the advancement of knowledge is that it puts to bed the ancient canard that only the literate have a brain. Reading and writing is fine, but not necessary to thought as Pinker proves through exploring words and their relationships with those who use them. It sets no boundaries. That which is yowled by babes has the worth of the pronouncements of the aged. Pinker's examination has free range over all the languages in the world, whether chanted by humans, sung by birds, or grunted by beasts. We may write, as did Plato, but like Socrates, it is our use of words that reveals our thinking.

Return to Top

Commentary on Christine Kenneally's The First Word Commentary on Christine Kenneally's The First Word

If one lacks the time to learn from all the books about all the origins of all the languages of the world, The First Word is an alternative read. One suspects that Christine Kenneally read most of those volumes before she wrote her own three hundred page summary. She commands the subject with reassuring thoroughness. Better yet, she shows admirable restraint in balancing linguistic creationists against linguistic evolutionists, contentious partisans in the world of academe. Fair play and fair writing is her mantra. Let the reader decide. Kenneally's time frame is so vast, that that minor linguistic dispute is like watching competing roads vanish to a point in the distance.

This college student of fifty years ago was bewildered at the controversy. He forsook linguistics to read novels and study art. Kenneally is made of sterner stuff. She persevered. With The First Word she exploits the delightful panoply of language evolution to distill out the commonality of its origin. She writes lightly, almost translucently. Through her, one sees language as an organic whole that is separate from its users, but is dependant upon them for its survival. One recognizes that language adjusts to changing times, unlike mathematics, but similar to music.

Strange it is that the mathematician is drawn to music, for two plus two has always equaled four, cardinal numbers differ from ordinal, and C squared has forever equaled A squared plus B squared. Music overlays the past by drawing on the present, and music, like language, will die without the musician. "Oh!" One cries. "How did the chorus of Sophocles sing their lines?" Without singers, no music. Without speakers, no language, and as Stephen Pinker reveals, without language, no thought. The innocence of curiosity draws man ever deeper into the profundities of existence, so one feels intellectually unbalanced when one contemplates our distant past. The discomfort, iconoclastic in its nature, may not be well received. Kenneally dodges that bullet by saving her best conclusions, uncomfortable as they may be for some, for her final chapters.

Thankfully, the inevitability of knowledge gives those who follow the explorers of our past, freedom of thought and action. One is released from the absurdity of re-creating neolithic language when one writes a neolithic novel. What has changed in language over the past five thousand years is diluted and eclipsed by what has remained over the past five hundred thousand, or past five million years.

Early on, Christine Kenneally quotes Arthur Schopenhauer: "All truth passes through three stages. First it is ridiculed. Second it is violently opposed. Third it is accepted as being self evident." Good luck to her in laying The First Word upon the table to be examined.

Return to Top

|